Recently a friend encouraged me to use my blog to share things I’ve been studying, and since I recently completed the first year of an Open University MA in Classical Studies, I thought I’d share the end of year paper I wrote answering the question, ‘How important is an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology?’

I am hoping to write next year’s dissertation using material and literary remains from Roman Corinth to shed light on some aspect of the Apostle Paul’s correspondence with the early Christians there. Any comments and ideas would be welcome.

The first year of the course has been fascinating and successful for me and I’m really looking forward to the new session that starts in October. In the meantime, here’s the essay and I’d be happy to receive any thoughts on it.

Jared.

How important is an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology?

‘Artifacts can’t tell us anything about the past because the past does not exist. We cannot touch the past, see it, or feel it; it is utterly dead and gone. Our beloved artifacts actually belong to the present…

‘Somehow we have to take the archaeological materials that we have and through our questioning get them to give us information about the past.’ (Johnson, 2020, pp. 14 – 5, emphasis original; cf. Osborne and Alcock, 2012, p. 3)

It is in the light of comments such as Johnson’s that I will argue in this essay that an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology is crucial to obtaining the fullest information from material remains and for understanding the lives of which they speak. However, the question posed for this essay begs the answer to two other questions that we must first address: what is ‘the study of archaeology’; what is ‘an interdisciplinary approach’? (I shall pass over the additional question, what is a ‘discipline’? (Rives, 2010, p. 98), and assume that it includes every skill that can be deployed in this enterprise.) I shall explore answers to these questions and then examine how the two relate to each other using examples from the city of Corinth and its material remains: pottery, coins and an inscription.

The ‘study of archaeology’ has a significant history and the concept(s) of what it is today is very different from that of a century ago and more. What is it now and how has it changed over time? For a brief historiographical taxonomy of methods for the study of archaeology I will draw on the American School of Classical Studies in Athens’ (hereafter ASCSA) explorations at Corinth from 1896.

Three eras of archaeological method over the period are helpfully laid out in ASCSA’s site guide (Sanders et al, 2018 pp. 24-5). Initially, excavations at Corinth were focussed on topography. The study of archaeology was about where important buildings were sited: temple, agora, homes, roads, theatre and forum, and large teams of non-specialist labourers were used to clear the ground.

In the second quarter of the twentieth century, it was typological and chronological concerns that predominated (Aldenderfer, 2012, pp. 309-11). What kinds of artefacts were being found and how did they relate to each other and their wider context of place and time? Can we discern a chronology through similarities among the materials discovered, cross-referenced to the various sites where they were found? However, the same basic method of employing local non-specialists continued, with the attendant inherent risks.

It was not until the 1960s, under the directorship of C. K. Williams II and amid the intellectual ferment of the time, that the focus shifted from monumental aspects of archaeology to place the human at the centre. This period also coincided with the ‘democratic turn’ (Hardwick and Stray, 2011, p. 3) in Classical Reception Studies. Together they reflect on how these remains may have been used originally by the people of their time and what information they can impart to us about these people and the kinds of lives they lived. ASCSA has published its findings extensively over the decades.

This does not mean that topographical, typological and chronological evidence is no longer important. Rather, it is placed within a new context where the dynamics of human processes are at the centre. Where, in the past, methods may have been developed on an ad hoc basis, with little or no theoretical assessment (Johnson, 2020, p. 16), the 1960s onwards saw the development of a ‘New Archaeology’ (Johnson, 2020, pp. 13-37) that grew out of a sense of dissatisfaction with previous archaeological work, its theories, methods and aims. By placing people at the centre, Archaeology was becoming a sub-discipline of Anthropology.

It would be an error to assume that in the present day there is a one-size-fits-all approach to the study of archaeology. There are varieties of approach of both theory and method. Rather than being a feature that simply fractures the study, perhaps these can be seen as a development with a positive impact on our understanding of material remains. Alternative theories and methodologies focussing their attention on the same data/artefacts, and advancing alternative possible interpretations, can enlarge our understanding rather than diminish it.

What emerged early on from new archaeology were groups identifying as ‘Processualism’ and ‘Post-processualism.’ These emphasise ‘the linkage between biological organisms (humans) and their environment’ (Schiffer, 2012, p. 665), which includes the available technology. Processualism relies heavily, therefore, on social theories allowing patterns to be discerned towards understanding the structure and dynamics of a culture (Schiffer, 2012, p. 666). Its aims were to ‘be more scientific and more anthropological’ (Johnson, 2020, p. 23, emphasis original), and its interest was in the community. Post-processualism is less of an identifiable ‘school’ and more of a movement of protest against what is seen as too positivist philosophical underpinnings of Processualism. Post-processualism presses the role of the individual as agent, provoking processualists ‘to embrace long-neglected research questions about, for example, ideology, power, and class, and to seek rigorous methods within a scientific epistemology to answer them.’ (Schiffer, 2012, p. 666)

The ‘study of archaeology,’ therefore, is a moving target, with theory and method in constant development and interaction. And if our ‘beloved artifacts’ cannot speak for themselves, how may we elicit and interpret the information they can divulge? Only by employing as wide a range of present-day disciplines as possible, that help to answer the many questions we may have – the more questions, the better (my own questions will be exemplary rather than exhaustive). Our present-day theories and methods need to be brought to bear not only on what is being discovered now, but also on remains recovered by previous generations of archaeologists. There will be lacunae in the chain of evidence and therefore no present-day investigation of previously discovered remains can be as rigorous as investigation on those found in situ today. The picture will be incomplete, but then the picture is always incomplete because the past cannot be recovered. And tomorrow’s advances in theory and method will be applied to today’s discoveries. We must make sure that as much data as possible is recorded and saved so that tomorrow’s advances will have as much as possible to work with.

It is important to note at this point that we do not need to provide detailed answers to all the questions we may have about artefacts referred to in this paper, only to illustrate the disciplines needed to answer them. However, from the literature available we will be able to indicate some answers. It is to how we can interrogate material remains that we now turn.

The material remains uncovered by ASCSA at Corinth include a wide variety of artefacts (see the range of essays in Williams and Bookidis, 2003). In truth, archaeology has always required people of different disciplines to carry forward its work, such as classicists, geographers, historians, specialists in pottery and numismatics, and people fit to dig. However, the extent to which disciplines cooperate will determine the extent of the information retrieved and how that information is interpreted. At this point, there is a basic question about the terminology we should use to describe this cooperation: should we speak of it as ‘multidisciplinary’ or ‘interdisciplinary,’ or do they mean the same thing? Both the ‘multi’ and ‘inter’ prefixes have a legitimate input to the cooperative concept: ‘multi’ reflects the wide range of disciplines that must be brought to bear; ‘inter’ reflects the nature of the interaction among these disciplines. The literature tends to use ‘interdisciplinary’ (e.g. Schaps, 2011, p. 12), but ‘multidisciplinary’ also appears to be implicit in how the term is used. Deciding on the more appropriate term is not easy. To illustrate my own understanding of the nature of the cooperation needed I will describe two scenarios. In the first, an artefact from Corinth is taken to a university and passed round several departments, each of which applies its own discipline to the artefact and writes an independent report on it. Thus, it is studied from the point of view of a multiplicity of disciplines, but without real interaction among them. In the second, an artefact from Corinth is placed on the table in a university conference room and scholars from various disciplines gather round the table. Each describes the artefact in terms of their discipline, but they are questioned and challenged by the others round the table so that the description is clarified (or complexified?) as far as possible through present theory and method. Only one report is written (although minority reports may be required to deal with competing interpretations). It is this second scenario I have in mind when I use either ‘interdisciplinary’ or ‘multidisciplinary’ to describe cooperative approaches. But which disciplines should sit round the conference table? That will depend on what is sitting on the table.

In the early years of the latter half of the twentieth century, there was a push to make the study of archaeology more rigorously scientific with new disciplines added to the mix, and we could now include such activities as soil analysis, carbon dating, DNA analysis and so on. But in the later years of the century, social sciences were also being adduced to interpret evidence: sociology, psychology, anthropology and others (Schaps, 2011, p. 12-3; Rives, 2010, p. 102). This gave rise to tensions that remain to the present day between the philosophical theories and methods of two very different kinds of scientific inquiry, and what can be known for certain through their application to material remains.

The disciplines needed to interrogate Corinth and its material remains will vary according to the remains being considered. Thinking first of Corinth as a whole, situated in Achaia on an isthmus, the Greek city was destroyed by the Roman army in 146BC, and largely uninhabited until Julius Caesar re-established it in 44BC as a Roman Colony that quickly grew in wealth and influence. But let us pause. How do we know this? Why did these things occur? Here we can bring to bear some of the more traditional disciplines of classical inquiry: geography and history, to reflect on the importance of Corinth’s situation and to investigate the story of its destruction and refounding, from ancient writers such as Strabo (1927, Geography, 8.6.20-3) and Pausanius (1918, Description of Greece 2), to the present; Latin and Greek, to translate annals, archives and inscriptions that may tell us who the colonists were, why they were sent and the constitution under which the Roman city existed (for inscriptions, see Kent, 1966); experts in the workings of the Roman Army who may be able to shed light on how the army related to every aspect of life in the Empire, including colonies (Pollard, 2010). But even this list of disciplines will only scratch the surface.

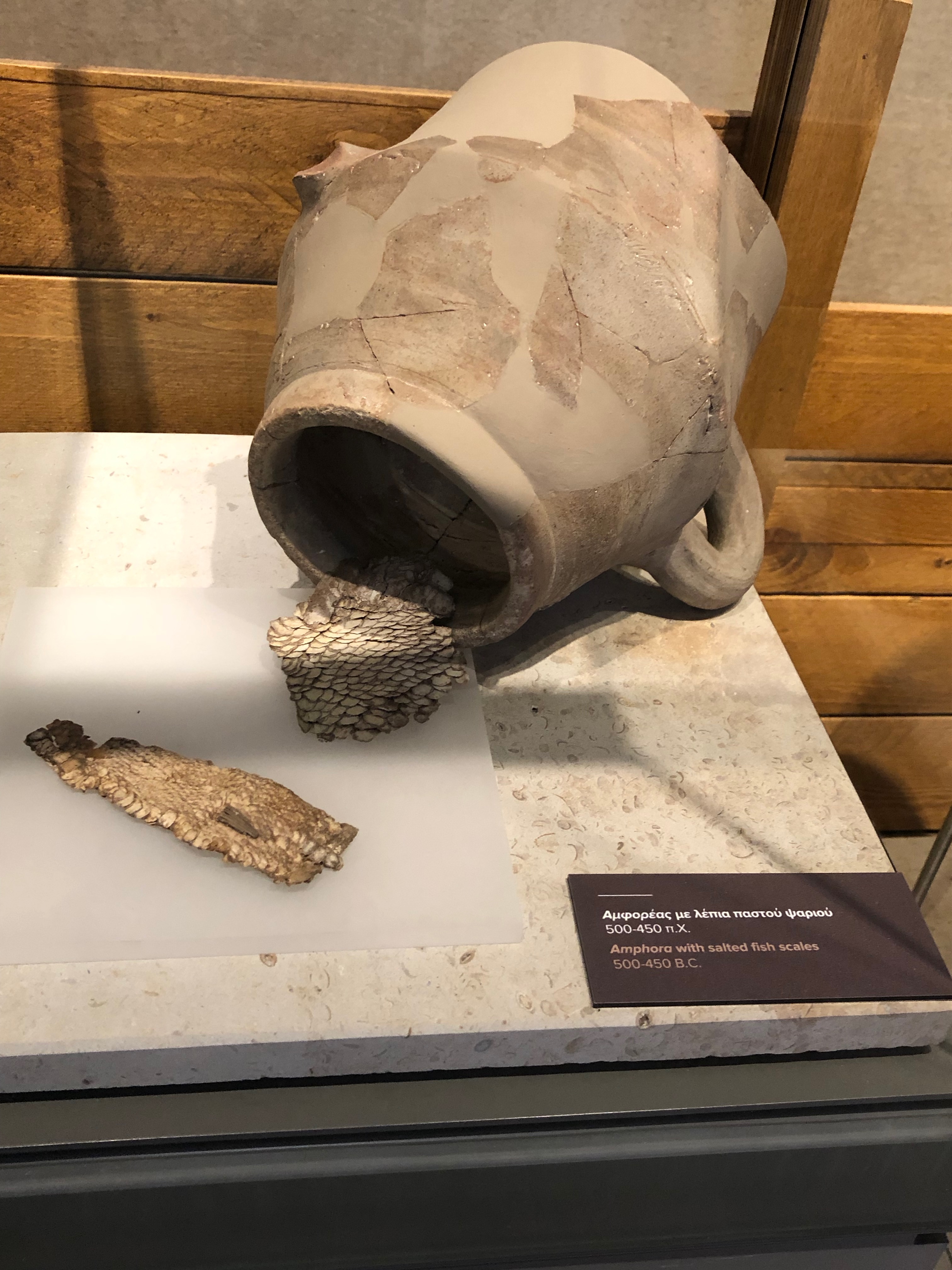

Let us now take three examples of artefacts found on the site of Ancient Corinth to exemplify how an interdisciplinary approach is needed: pottery, coins and an inscription. Corinth was known as a mass producer of pottery from pre-Roman times (Risser, 2003, p. 157; see Figs. 1-3 in the Appendix), and many examples have been found that span time from the eighth century BC, through Roman Corinth and beyond, within the city and elsewhere (see chapters 8-12, 19 and 24 in Williams and Bookidis, 2003; for examples, see Figs. 2 and 3 in the Appendix). How might we know if pottery found within the city was made in the city or elsewhere? What can we tell from residue within a pot? How can we discern the age of pottery and to which era it belonged? What about pottery found elsewhere, but made in Corinth? Can we identify it, and if we can, what does this say about the influence of Corinth in the eastern Mediterranean? We need disciplines that will help us understand processes of collection of raw materials, product design and decoration, and economic activity across the region, all diachronically over centuries. But, for a moment let us focus on one discipline relating to clay.

Clay is the basic material of ceramic production and there are deposits of various kinds around Corinth. Each deposit has clay minerals in varying quantities, and these can be identified by using X-ray diffraction. However, after clay has been fired, other methods must be used, such as ceramic petrology and chemical analysis (Whitbread, 2003, pp. 2-3). All these disciplines are highly scientific and technical and are not part of ‘everyday’ archaeological activity. However, they are necessary tools for grasping some of the significance of Corinthian pottery over a prolonged period. Working together they can begin to build a picture of the role this pottery played in lives across generations.

Ancient Corinth produced its own coins (for examples, see Fig. 3 in the Appendix), and Roman Corinth also had its own provincial mint from its foundation until the accession of Vespasian. It was re-established under Domitian, but minted fewer coins from then on. The coins were made of bronze, for which Corinth was renowned, but they have often been found badly corroded in the soil (Wallbank, 2003, p. 337).

Bradley Bitner writes that four methodological considerations are relevant to engaging with Corinthian coinage in Roman times (Bitner, 2015, p.161-76), and these are well worthy of consideration. First, this is Roman provincial coinage, rather than Imperial coinage, with implications for the time-frame, geographical setting and political authority under which the coins were produced. Second, we must measure what we can of the minting process from mining of the metal to the size of the coin and its image. And we must do this cognisant of the civic life of the city and its duoviri for ‘not only does the money give us evidence for the men; the men gave us the money.’ (p. 164) Third, there needs to be investigation of how Corinthian coinage circulated within the wider area to gauge its impact on the regional economy. Finally, since numismatic iconography presents a face to the world, there needs to be careful examination of coin stamps to try to understand how the city saw itself, and, perhaps more importantly, how its officials wanted it to be seen by the world.

What questions, then, might we ask of these coins to shed light on the life of the city and its surrounds? How big are they? Of what value are they? How pure is the metal? Is there metal debasement over time? What is the significance of the iconography? Might the number of coins found provide any indication of the strength of economic activity locally? Were Corinthian coins found elsewhere, and/or non-Corinthian coins found in Corinth (see Appendix, Figs. 4 and 5)? What might that tell us of economic activity in the region? How might the iconography of coinage cast light on the civic identity of Corinth? Can interpreting duovirate coinage help us put together a Corinthian chronology and/or tell us something about its officials? Could a longitudinal examination of the iconography of Corinthian coinage tell us anything about the trajectory of the city’s relationships with Rome and Greece? Could the residual material adhering to the coins hold any DNA that, when analysed, could shed light on those who handled it? It is clear that many of these questions may be addressed in ‘everyday’ numismatics, but the net must be cast more widely to include metallurgy, economics, DNA analysis, iconography and the sociology of urban and imperial identity. Interdisciplinarity is a sine qua non for this inquiry.

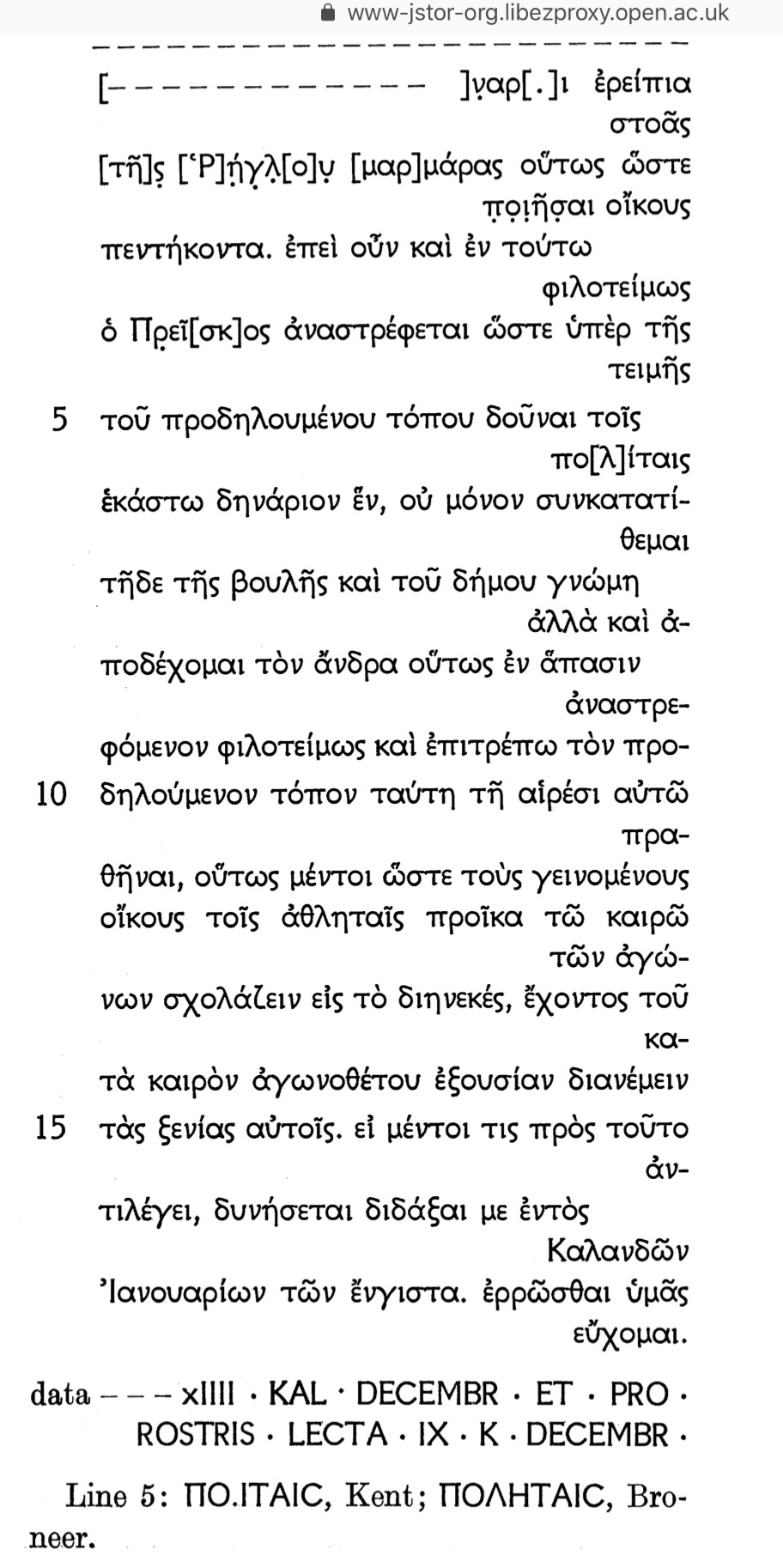

We turn, finally, to an inscription. As noted above, from 44BC Corinth was a Roman Colony. The question of language, therefore, arises: how were Latin and Greek used in Roman Corinth, and how did the relationship between the languages develop? The inscription in question (Kent, 1966, p. 120 and Plate 26, see Appendix, Fig. 6), inscribed on a limestone block, was read on 23 November of an unknown year in the second century AD. Thirty-one lines of it are in Greek, and one, final, line in Latin. It appears to have been official communication (Kent, 1966, p. 120; Bitner, 2016, p. 185). In addition to the need for translation, there are questions prompted by this inscription. Where did the limestone come from? Was the inscription commissioned and written elsewhere? Who commissioned it, and why? Why was most of it in Greek? Why, with so much Greek, was there any Latin at all? Was the Latin an official archival reference? What light could this inscription shed on the ongoing relationship of Roman Corinth with Rome and Greece?

For us to answer these questions we need not only translators and historians, but also geologists and chemists, who may be able to identify possible sources for the limestone. We need experts in Roman administration in the colonies to shed light on why and how public announcements were made, what style of fonts were used in them, and how they were recorded for posterity. Only thus will this inscription give up more of its information and speak to us about the city where it was read.

It is clear from the range of skills needed to answer the questions we have raised about the artefacts from Corinth that wide-ranging disciplines – humanities, historical, linguistic, scientific and social-scientific – need to be applied to help answer them, and most of these disciplines are not ones in which humanists and social scientists have particular training (Wylie and Chapman, 2015, p. 4). Specialists are required, though not all specialists will be required on every occasion. Regardless of how many are involved at any one time, it is the depth of their interaction that will lead to greater understanding. The answers they give to the questions must be assessed and interpreted against the backdrop of our wider knowledge of the historical and cultural context in which the artefacts were found. What stories do we think they tell? Which leads us to interpretation.

The issues surrounding the interpretation of facts are not easy. ‘Material evidence is inescapably an interpretive construct; what it “says” is contingent on the provisional scaffolding we bring to bear.’ (Chapman and Wylie, 2016, p. 6) Our personal identity, historical situatedness and biases place us in danger of constructing our interpretation of the evidence in ways that are not justified. Of course, others are in the same boat, but as we explore possibilities together from a range of disciplines and personal situations, a more fruitful and nuanced picture can emerge. Interpretation, therefore, must be ‘an ongoing iterative process’ (Wylie and Chapman, 2015, p. 13) that must be approached with ‘epistemic humility’ (Chapman and Wylie, 2016, p. 10).

In conclusion, it is only as disciplines work in humble cooperation, informing and challenging one another’s work, that a fuller picture can be painted of the life and social settings of ancient communities. Schaps broadly agrees with the assertion that no one scholar can have the required range of expertise and, as a consequence, he sees the need to ‘produce less departmentalized classicists.’ (Schaps, 2011, p. 13).’ To achieve this, Wylie and Chapman urge that archaeology must be ‘a dynamic trading zone…building an expansive network of technical, empirical, theoretical exchange (2015, p. 17) This is an ambitious aim for carrying forward the study of archaeology so that it may give us the best possible insights to the lives of people in the past. An interdisciplinary approach is not simply important; it is essential.

Jared W. Hay, May 2019

Bibliography

Alcock, Susan E. and Osborne, Robin, Editors (2012), Classical Archaeology (Second Edition), Blackwell, Oxford.

Aldenderfer, Mark (2012), ‘Typological Analysis,’ in Silberman, Neil Asher (2012), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition, Vol. 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Bitner, Bradley J. (2015), ‘Coinage and Colonial Identity: Corinthian Numismatics and the Corinthian Correspondence,’ in Harrison and Welborn, 2015, pp. 151-87.

Bitner, Bradley J. (2016), ‘Mixed Language Inscribing at Roman Corinth,’ in Harrison and Welborn, 2016, pp. 185-218.

Chapman, Robert and Wylie, Alison (2016), Evidential Reasoning in Archaeology, Bloomsbury Academic, London.

Chapman, Robert and Wylie, Alison, Editors, (2015), Material Evidence: Learning from archaeological practice, Routledge, London/New York.

Hardwick, Lorna and Stray Christopher (2011), A Companion to Classical Receptions, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford.

Harrison, James R., and Welborn, L. L. (2015), The First Urban Churches 1: Methodological Foundations, SBL Press, Atlanta.

Harrison, James R., and Welborn, L. L. (2016), The First Urban Churches 2: Roman Corinth, SBL Press, Atlanta.

Johnson, Matthew (2020 – sic), Archaeological Theory: An Introduction, Third Edition, Blackwell, Oxford.

Kent, John Harvey (1966), Corinth: Volume VIII Part III: The Inscriptions 11926-1950, ASCSA, Princeton.

Osborne, Robin, and Alcock, Susan E. (2012), ‘Introduction’ in Alcock and Osborne, 2012, pp. 1-10.

Pausanias (1918), Description of Greece: Books 1-2, LCL, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA/London.

Pollard, Nigel (2010), ‘The Roman Army,’ in Potter, 2010, pp. 206-27

Potter, David S. Editor (2010), A Companion to the Roman Empire, Blackwell, Oxford.

Risser, Martha K. (2003), ‘Corinthian Archaic and Classical Pottery,’ in Williams and Bookidis, 2003, pp. 157-65.

Rives, James B. (2010), ‘Interdisciplinary Approaches,’ in Potter, 2010, pp. 98 – 112.

Sanders, Guy D. R., Palinkas, Jennifer, Tzonou-Herbst, Ioulia, Herbst, James (2018), Ancient Corinth Site Guide (Seventh Edition ), American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton.

Schaps, David M. (2011), Handbook for Classical Research, Routledge, London/New York.

Schiffer, Michael Brian (2012), ‘Processual Theory,’ in Silberman, Neil Asher (2012), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition, Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Silberman, Neil Asher (2012), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition, Vols. 1-3, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Strabo, (1927), Geography: Books 8-9, LCL, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA/London.

Wallbank, Mary E. Hoskins (2003), ‘Aspects of Corinthian Coinage in the late 1st and early 2nd Centuries A.C., in Williams and Bookidis, 2003, pp. 337-49.

Whitbread, Ian K. (2003), ‘Clays of Corinth: the study of a basic resource for ceramic production,’ in Williams and Bookidis, 2003, pp.1-13.

Williams, Charles K. II and Bookidis, Nancy (2003), Corinth: Results of excavations conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. XX, Corinth, The Centenary: 1896-1996, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton.

Wylie, Alison and Chapman, Robert (2015), ‘Material Evidence: Learning from archaeological practice,’ in Chapman and Wylie, 2015, pp. 1-20.

Appendix 1

All photographs taken by the author, except Fig. 6.

An exhibit in the Ancient Corinth Museum.

An exhibit in the Ancient Corinth Museum.

Fig. 4 (top half) Examples of pre-Roman Corinthian coins.

Fig. 5 (lower half) Examples of pre-Roman non-Corinthian coins found in Corinth.

Exhibits in the Ancient Corinth Museum.