Family Tribute from Jared Hay 28 October 2019

It’s hard to believe that it’s already a month since we lost Mum. To mark the moment, here is the tribute that I gave at her funeral, more or less as it was given. There were a few more spontaneous moments. Kev Murdoch also gave one on behalf of her grandchildren. Last Sunday, 17th, saw what would have been her 100th birthday.

May she rest in peace and rise in glory.

Introduction

Echo Jack’s thanks to our Christian friends in Bethany Hall – Mum had many friends here and Dad had many relatives!

Book of Liturgies from Presbyterian Church in the US: Funerals – Service of Witness to the Resurrection. Yes, this is a sad time, but also a time of hope. Paul: 2 Cor 4: ‘we know that the one who raised the Lord Jesus from the dead will also raise us with Jesus and present us with you to himself.

16 Therefore we do not lose heart. Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day. 17 For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. 18 So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.’

Outwardly, mum was wasting away – we could see it before our eyes. But the infirmities of our mortality cannot erase the work of the Holy Spirit in our inner beings, preparing us for resurrection.

Names and History

It’s impossible to sum up 100 years in a few minutes, so this tribute will be very selective. Mum was known by several names: Annie Woods, Annie Hay, Mum, Aunt Annie, Gran Hay, Grannie Annie and even Battlin’ Annie. She was born on 17 November 1919, the year of the Treaty of Versailles, which brought the Great War officially to an end. That means her family – Jared Woods and Mary Bryan, her father and mother, with her six brothers and sisters, were brought up in the aftermath of that war, came through the Great Depression of the late 20s and 30s, and WWII. No wonder those who survived were a resilient generation.

They lived in 8 Boyd Street – a two roomed house with a w/c, no bath, and a tiny kitchenette. The main room had two bed recesses, and they often rented out the front room, for some time to Uncle Jim and Aunt Mary Hay, before they left for Canada.

I don’t know how or when Mum came to faith in Christ, but she did, and was involved for the rest of her active life in Bute Hall, along with her sisters Jean and Nessie. These three sisters married the remaining three Hay brothers – John, Bill and Bert, Mum and Dad marrying on 22 March 1945.

They set up home with Granny and Grandpa Hay in 2 Crawford Avenue. There, Mum helped to nurse Granny Hay in her final illness, and for around two years coped with Grandpa Hay after a major stroke until his death in 1962. She had a lot of caring and home nursing to do, but she did it well, and to Grandpa’s satisfaction. At our holiday time, when two of his own daughters came to look after him, he told them that together they couldn’t do it as well as Annie on her own!

Crawford Avenue was the place where our family was formed – Jack arrived first – he’s so much older! – then me and then Moyra. Older members of the wider family will remember New Year gatherings, after the Ayr Conference, when the house would be full of Hays, Pickens, Hills and Andersons of at least two generations, for whom Mum spent days catering. The house would smell of ox tongue, boiled ham, Scotch Broth and a wide range of baking. How she did it I’ll never know! But these were good times and taught us the importance of family.

We moved to St Quivox Road in the mid 1960s and that home too became a place of rich hospitality. Sunday nights, Thursday nights, family, friends and visiting preachers would often sit round the table or in the Lounge, and Mum always had lots to set before them. When Papa died, I asked our Ian what he remembered of him. Ian said, ‘The smell.’ By which he meant the smell of tomato plants and geraniums and the like! One could say the same of Gran, except about baking. When Jack and I met up to chat about today, we were served a café latte (or milky coffee as we used to call it!) with a small piece of shortbread. I said to him, this will not be as good as Mum’s! While not a very adventurous cook, her baking was amazing – sponges, angel cakes, pancakes, oven scones, griddle scones, but above all, her shortbread. I have never tasted any as good, and never expect to!

As a very young woman, Mum served in Annie Fraser’s milliner’s shop in Prestwick, but during WWII, she moved near Glasgow as a worker in a munitions’ factory. Rather her than me! Well after the children were up and working, she returned to employment as Dad’s secretary and partner in the weighing machine business they had taken over. While they often had done things together, they now did almost everything together, at work and later in retirement. Not everything was sweetness and light all the time, but they were a couple who loved each other deeply and worked well together.

For Mum and Dad, it was important that we had a family holiday every year, usually a week on the Yorkshire or Lancashire coast, often visiting brother Jim Woods and his wife Margaret in Waddington, and sometimes taking a trip to Crawley, to see brother Humphrey Woods and wife Phyllis. Nearer home, while Nessie carried more of the load of looking after Grannie Woods and Johnstone, Mum was always in and out of Boyd Street too. The place was never upgraded in their time to avoid rent increases, so Johnstone went to Broompark Avenue or St Quivox Road for a weekly bath, whether he needed it or not. There was a real commitment to her family in a whole variety of ways.

That commitment was also shown to her children, in a whole range of ways, in good times and bad. She welcomed Lillian, Sandy and Jane into the family – perhaps Sandy with some reservations! But Lillian was more than a daughter-in-law to her; she was a friend, companion and often a carer for Mum.

Mum also played her part in Bute Hall over many years, not only in the kitchen. Often Annie and Nessie would visit women in hospital or ill at home, or those who had been bereaved. Even after Dad died, if she could be, she was there on Sunday mornings and Thursday nights.

Themes and sayings

Ok, it’s time to be more succinct. Here are some themes from Mum’s life that we remember and for which we give thanks.

Her smile: when I posted on the Friends of Berelands Facebook page that Mum had died and how grateful we were to the staff, so many of them posted about her smile, what a lovely lady she was, and the sense of contentment she had. You only had to say to her, ‘Mum, we’re going to take a photograph,’ and she would run her fingers through her hair and put a big smile on her face.

Her handbag: she never went anywhere without it, even in Berelands (staff mentioned it!) and it was a bit like Mary Poppins bag – there was an awful lot of stuff in it!

Counting cards: she would have been delighted with the number of folks to responded to the various Facebook posts, because every birthday or Christmas she would count them and let us know how many she had received. It was an annual competition!

Lurpak butter: occasionally she would go on a diet, but one thing she would never give up and that was Lurpak butter. We used to tease her that this was not good for her diet, but she assured us that the doctor had said it was good for her health and her weight.

Dominoes: anyone who visited St Quivox Road for any length of time, or just for an evening visit, could be dragooned into playing dominoes, and Mum played it so often that she was a Past Master. It was rare for us to beat her. Stuart Hay from Canada remembers being thrashed at dominoes by her!

Tea: Mum loved her cup of tea – never on its own, and never brewed for long. Dad used to call it ‘lighthouse tea’ because it was blinking near water. But even to the end she enjoyed her tea, and one of the ‘sacred moments’ as we visited her about a week before her death, was to help her sip her cup of tea.

Faith: Mum didn’t really enter into much conversation about her faith, but she absorbed what she was taught and put it into practice in her life. She was a disciple of Jesus who sought to practise love for God and neighbour.

What’s the Story: any time you phoned Mum, after a bit of a gap, this would be her opening gambit. Dad rarely answered the phone, this was Mum’s domain. She wanted to know what was going on in your life and took a real interest in all that was happening: health, events, how the family were doing, the lot. Whether she realised it or not, she bought into the idea that, as Christians, we are living in a Big Story that will end in New Creation.

You’ve just got to get on with it: after Dad died, Mum rarely talked about him unless someone else raised the subject. Moyra and Sandy were so concerned about that and they tentatively raised the issue with Mum. Her response was, ‘You’ve just got to get on with it. There’s nothing else for it.’ This was the generation who had seen all these horrific global events, and a woman who had experienced the sadness of miscarriage. She could either feel sorry for herself, or she could make her own way into the future.

Everything’s mixed with mercy: anytime we heard a really sad story, she always saw some kind of circumstance that mitigated the sadness, and this is what Mum would say. We experienced it in her life when Moyra died, that Mum herself was not able fully to take in the great loss that she had suffered. And in her own death, after months of constant decline, the mercy was the great compassion and care of the staff at Berelands, who loved her and will miss her.

Conclusion

As I said earlier, you can’t sum up 100 years in a few minutes and you will have your own memories of Mum. But these are some of mine. However, you may have noticed that there is a large gap in my telling of Mum’s life, and that is her grandchildren. They were all dear to her and she to them, and now Kev Murdoch, my Anglican nephew, is going to share a perspective on Mum’s life from the point of view of her grandchildren.

I don’t think that I’ve ever had such a marked change of gear in my life than that between yesterday and today. Yesterday was Mum’s funeral service, and a joyful celebration of her life it was. Today I’m having to adjust to leaving the country for what I hope will be the learning experience of a lifetime. It’s been an awkward transition, but doing nothing but travelling has helped.

It was another early rise to be out the door by 7.15am and thankfully, although the bypass was busy as usual early in the day, we made it in good time to the airport and it was a smooth transition through security. Flying KLM to Schiphol then on to Rome, so two flights, which both left on time, were well organised and both had very smooth landings – I passed my compliments to both pilots. Then things got a bit hairy. I inadvertently (!) bought a ticket for a minibus taxi to Termini instead of getting a train to Trastevere. It nearly cost me my life! The bus was driven by Mad Max, and with 8 + driver on the motorway he was doing 160 kph, ie over 100 mph. I think if I had been in the back I would have been sick, but it was scary enough seeing the tailgating from the front. And he was on the phone hands-free every minute of the journey. One bloke jumped out and got his bag from the boot when we stopped at a red light in the city centre! Thankfully, we arrived safely at Termini.

When looking for a train to go somewhere, it always helps to look at the departures rather than the arrivals. Blithely watching the wrong board, I suddenly realised my mistake, and that the train I wanted was about to depart from a platform that was hundreds of yards away. I gave up running and prayed that the train would be late. My prayer was answered!! It was running ten minutes late and I managed to get on AND get a seat on what was a really busy train. Express it was not, but at least it got me to my destination and my life was not under threat.

My B&B is a very modest little place with helpful staff and not very expensive. I was given a bit of guidance on where to eat and had a nice meal, the main course of which was a 75cl bottle of water and a bottle of lager. Hydration levels were running low. Now I’m chilling out ready to head for bed and what I hope will be a good sleep before embarking on the Jewel of the Seas for this great adventure.

Over the last few weeks I’ve been giving some thought to how some NT letters contain ‘Household codes’ and what we are to make of them today. Why and why now? The ‘why’ is personal, so I won’t bore you with it, but the ‘now’ is because, while I was trying to have a snooze, I started putting it together in my head. I had to get up to do a brain dump on to the computer in order to clear the mind. The snooze had to wait. I should say that what I am arguing against is what I was brought with and what I once embraced.

Rather than look at the codes in depth I want to share a few broad-brush thoughts so that we can put them in a more secure context in order to interpret them. Down through the centuries they have been used and abused in such a way as to bring dishonour on the name of Christ, not least the way they have been used in the Church to justify inequitable power structures.

The most common code that is used is the one in Ephesians 5:21 – 6:9 probably because it is longer and more detailed than the similar one in Colossians. It addresses wives and husbands, children and parents, slaves and masters, but in order to transfer any meaning to our own context, we need to understand how they spoke into their own time.

Some questions.

What was Paul trying to do when he wrote them?

What form do they take?

How does the culture in which they were written shed light on their form and content?

Let’s take the last question first and the answers to the others will be threaded through.

It’s crucial to understanding the cultural context of the NT to realise that Greco-Roman culture within the Roman Empire was highly stratified and moving from one layer of society to another was near impossible – perhaps the main exception to this was the way in which slaves could experience manumission and become free. Even then, one was still a freed slave. But the main feature of social structure, from our perspective, was (and this is a gross oversimplification, but not one without some force) that there were people who mattered and people who didn’t. Among the people who mattered, there were those who really mattered – the élite, a small group whose power and wealth were beyond the imagining of the rest and who basically governed the Empire. Then there were those further down, who still mattered, but not nearly as much as the élite, such as wealthy businessmen and local power brokers. While there were some influential women among the élite, really, they didn’t hold the power. Men held the power. Men were Emperors. Men were Senators. Men were the heads of families. Men were the decisionmakers. Men really mattered.

Those who didn’t matter within the family, in terms of powerbroking, were women, children and slaves – and slaves really didn’t matter at all. In fact, they were not people, they were chattels to be treated as their masters saw fit. Of course, there were some who became special to their master, like Cicero’s secretary, and some prided themselves on being a slave of the Emperor, rather than that of an ordinary household. But still the master could do as he pleased. It is hard for us, even with experience of African American slavery still in the public consciousness, to understand how endemic slavery was in the Roman world. The economy was built on slavery and it would have been a poor household that did not have slaves.

Within some communities, such as Jewish society, women had more of a place and a role in the family. But in the grand scheme of things, across the societies governed by Rome, women fared badly in decision-making processes of home and city, and children even more so.

So, the first thing to notice is that Paul spoke both to those who didn’t matter in wider society – and he spoke to them first – and to those who did matter. I find it astonishing and enlightening that Paul addressed both groups, given the imbalance of power among them. Why did he do this? Here we have to do a bit of wider reasoning and acknowledge that ‘the text’ we are reading and interpreting is not only the words on the page before us, but it includes the context into which it was written. Only by exploring that as fully as we can is it possible for us to understand the force with which Paul’s words would have been received.

I believe that Paul would not have written such household codes unless he thought the families needed to hear them, and hear them as an expression of what it means to live as a Christian family, whose allegiance is to Christ and not the Emperor or the society he led. In other words, Paul was trying to shape and to change behaviour. Whose behaviour? The easy answer to that would be, ‘Everyone’s behaviour.’ And to some extent that is true. But as interpreters of Scripture, we seek to explore the possible impacts of Paul’s words on his readers. So, when we ask, ‘Whose behaviour was most in need of change?’ then the answer is sharpened, particularly when we add to the mix, Paul’s iconic overturning of the stratification of Roman society to illustrate who may enter and live in the Kingdom of God. This is found in Galatians 3:26-29, ‘ 26 So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith, 27 for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. 28 There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. 29 If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.’ For entry to the Kingdom of God, the social divisions of religious origin, status and gender have been set aside. Everyone who belongs to the body Christ matters equally, even if there are still some differentiations regarding the roles played within that body.

When we reflect on how this might influence what Paul was trying to do, I would argue that he was wanting to, and needing to, speak to men about how they wield power in relationships – specifically husbands, fathers and masters.

The form that the codes take is interesting, because he writes first to those who didn’t matter. He does so invoking ‘the Lord’ but otherwise in fairly traditional cultural ways within Roman society. One can imagine those who did matter listening to this being read at a church gathering and sitting back complacently thinking, ‘Good for you, Paul. That should keep them in their place!’ This I would identify as Paul’s ‘Gotcha’ moment. It is in the second section of every twinning, written to those who do matter, that the real call for change is made. It is remarkable that they were written at all, for, in such a culture, the men had the real power in ordering the lives of the household. And the codes are written in such a way that what precedes the address to the powerbrokers, though not repealed is at least ameliorated to an extent. Or perhaps it would be better to say that those who do matter are being told to behave in such a way that those who don’t matter really matter, because they matter to God. The social and cultural norms are being realigned within families of faith to reflect the social nature of the Kingdom of God.

Of particular interest to the form of the code is the beginning and the ending. The start instructs the church to ‘submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.’ Whatever ‘submit’ means in this instance, there is to be a mutuality about it that is often insufficiently reflected in how the code is to be applied to the present day. Indeed, the word does not occur in the Greek text of Ephesians 5:22, but is read over from v21 in English translations.

The ending states that ‘there is no favouritism with [God].’ This is especially written to masters – one can imagine some outrage that slaves matter to God as much as masters – but is implicitly applicable to each twinning. To God, those who ‘don’t matter’ matter every bit as much as those who ‘do matter’ and the Christian family is to be the place where this reversal of Roman culture should be seen.

So, it seems to me that taking the household codes and transferring them to today’s world cannot be done without paying due attention to several things:

▪ the prevailing culture was one in which men had overwhelming power within family relationships;

▪ the Gospel expresses a society in which everyone matters to God;

▪ Paul’s rhetorical purpose in writing them included changing the attitude and behaviour of men within household relationships.

These, then, were radical codes that, rather than keep people in their place, undermined the social structure of the Roman Empire. The danger is that, by not understanding them in context, we use them to subjugate people today and thereby continue to solidify unjust social structures.

Heading into Honfleur of an evening to eat, I was wearing my ‘Still European’ hoodie, noted positively by a number of people. But on the way I began to think about Brexit, and a major slogan of the Leave campaign: Take Back Control. A premise behind this slogan is that the big bad bureaucracy in Brussels has taken over all our decision-making processes so that we can no longer make any decisions for ourselves. I can see that lots of decisions that affect the UK are made in Brussels, but we have had a share in making them either through elected representatives in the EU Parliament or in the Council of Ministers. However, I do know that the EU is not a perfect bureaucracy and can never be, although it could be improved.

What occurred to me in the car as I was driving is that there are two other underlying premises that are always unstated and never examined by those who promote Take Back Control. These are:

I question both of these premises and want to give them a brief examination to support my assertion.

When was the last time the UK had full control of our decision-making processes? I guess that depends on how one defines control, and the answer to this may vary from one area of public policy to another. But in the grand scheme of things, we have not had total control of our national life since before the Great War. That was also the era when the USA began to play a greater part in global affairs. Since America’s commitment to the Allied cause in both World Wars (not, it has to be said, out of anything but self-interest) the UK has not had total control over its decision-making processes – the indefensible Suez debacle in 1956 is a prime example, long before we were part of the developing European enterprise. Our existence among the global powers has been one in which we have had to take the opinion and policies of others into account, which means we cannot simply do what we want – we have not had total control.

That being the case, we are unlikely to achieve taking back control if we leave the EU, but the situation would in all likelihood be worse that it was when we joined. Since then, the commercial world has become more globalised: banks, manufacturers and IT companies will take their business to the place that’s best for them, and if we don’t have sufficient integration with other large markets, they will go their own way. Having sufficient integration would mean not having total control since we would have to adhere to the conventions/specifications of others to gain access to markets – we can’t just say, ‘We use Imperial measures: take it or leave it!’ Furthermore, having left the EU we will be in a much weaker bargaining position relating to trade agreements. Other nations, especially strong nations like the US, will make their demands upon us to achieve a trade agreement, which will inevitably mean not having control of everything that crosses our borders and into our markets.

There are few, if any, major aspects of public life over which we would have total control – even in the area of taxation, we depend on cooperation with others about how to tax large corporations spread across several continents. Taking total control is more likely to drive them away, rather than attract them. And if we structured our tax-system to attract them, we can be sure that other nations will seek to undermine that in ways that are beyond our control. In strategic defence, monetary policy, banking, taxation, trade and much else, we are, and will be, dependent on others for cooperation to make things work for us. We do not and will not have the kind of control that the Leave campaign assert we will.

Sadly, ‘Take back control’ is a good soundbite that appeals particularly to those of an Imperial mindset who do not realise that these are days that cannot be recovered, even if we wanted to. By the time it is realised that we cannot take back control, it will be too late, and we will have lost whatever shared control we had, finding that those with whom we cooperated are now our competitors. They will not go easy on us.

Paul’s Greek – staccato?

As it happens in the annual schedule for covering the GNT in a year, I’ve been reading 2 Corinthians recently, and (not being very proficient) have found it particularly difficult to follow at times. So, I was comforted to see this comment in the first ICC commentary on the letter by Alfred Plummer.

Alfred Plummer (viii): Readers will do well to study the paraphrases prefixed to the sections before consulting the notes. No translation, however accurate, can give the full meaning of any Pauline Epistle, and this is specially true of 2 Corinthians. The only adequate method is to paraphrase….

Near obsession with suffering and death (and what follows)

Reading it in Greek (so far up to chapter 6), which for me requires a more intense focus on the text than following in English, has given me the impression that spilling out of his heart is a whole lot of stuff to do with suffering and death – and what follows from that. I suspect that this is not simply to do with the rhetoric he needs to adopt to make his point to the Corinthians, but because of his recent experiences in Ephesus and elsewhere. There is a real sense that what these experiences have taken out of him bodily will result in his death rather than be around for the Parousia.

Paul’s Anthropology underneath 2 Cor 5

I think it’s unlikely that one can interpret Paul’s meaning in 2 Cor 5:1-10 without bringing to the passage as an assumption some kind of framework on Paul’s Anthropology. A key question here for me is this: Is it possible for a human being to exist as other than embodied spirit? The options for understanding the passage depend on how one answers this question. If yes, then the ‘building from God, an eternal house in heaven, not built by human hands’ can be the resurrection body envisaged in 1 Cor 15 received on the Day of Resurrection, and the immediate state after death will be disembodied spirit in the presence of Christ. If no, then it could be a new body received at death and perhaps we could say publicly revealed on the Day of Resurrection. I have come to the latter conclusion because I think that essential to Paul’s Anthropology is that to be human is to be embodied spirit.

Worrying about the unresolved tension with 1 Cor 15

There is no doubt that whatever position we take on the relationship between 2 Cor 5 and 1 Cor 15, there is a tension between them. Many have sought to resolve the tension over the centuries, but I haven’t yet come across a resolution that satisfies me. It seems to me, therefore, that the ancients were much less worried about loose threads in their thinking than we are, and they were happy enough to try to explicate according to the perspective from which they were seeing things: in this case Paul explaining things from the point of view of someone expecting to be alive at the Parousia in 1 Cor 15, and then in 2 Cor 5 from the point of view of someone expecting to die before the Parousia. All Paul’s letters need to be interpreted within their historical situation as far as we can know it – they are ‘occasional’ documents. So, perhaps we should be less inclined to build a watertight system of his thought.

OK, just to be clear, I’m not going to blog every day, but over the last few days, for a variety of reasons, I’ve been thinking about 2 Corinthians 5:1-10, trying to puzzle it out in the company of some commentators. I was thinking about it with the frailty of my nearly 100 year-old mother in mind, not to mention my own ageing body, and I think I managed to come to what is a coherent view of why what Paul writes here feels so very different to what he writes in 1 Corinthians 15. First of all, here’s the text of 2 Corinthians 5.

For we know that if the earthly tent we live in is destroyed, we have a building from God, an eternal house in heaven, not built by human hands. 2 Meanwhile we groan, longing to be clothed instead with our heavenly dwelling, 3 because when we are clothed, we will not be found naked. 4 For while we are in this tent, we groan and are burdened, because we do not wish to be unclothed but to be clothed instead with our heavenly dwelling, so that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life. 5 Now the one who has fashioned us for this very purpose is God, who has given us the Spirit as a deposit, guaranteeing what is to come.

6 Therefore we are always confident and know that as long as we are at home in the body we are away from the Lord. 7 For we live by faith, not by sight. 8 We are confident, I say, and would prefer to be away from the body and at home with the Lord. 9 So we make it our goal to please him, whether we are at home in the body or away from it. 10 For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each of us may receive what is due to us for the things done while in the body, whether good or bad.

One of the things we know about Paul is that he was a leatherworker who often made tents, with friends like Priscilla and Aquila. During the considerable time that he spent living in Corinth he must have made many for the travellers and entrepreneurs who passed through the city, as well as its residents. They were often used by those who travelled by ship to give shelter from the elements on deck. But they wore out and needed to be replaced.

There are at least two things that we can draw from Paul’s metaphorical use of tents here to describe the human body. The first is its mortality: like tents, bodies wear out. The second is life as journey/pilgrimage: it is easy to see an allusion to the Tabernacle of Exodus here – it was used in the desert and led people to the land of promise. It is the first of these that is primarily in mind (Paul’s as well as mine, I think!), and underneath the metaphor is the unspoken yet assumed view of Paul’s anthropology that to be human is to be embodied spirit.

Hitherto, in the light of 1 Corinthians 15, I had understood Paul to picture deceased Christians in disembodied spirits until the day of resurrection, when they will be given a ‘spiritual body’ like the resurrected Christ (1 Cor 15:42-49). I tried to view 2 Corinthians 5 in the light of that, and, like many others before me, found that difficult. How does an eternal ‘heavenly dwelling’ that is given at death relate to a ‘spiritual body’ on the day of resurrection? Has Paul changed his mind?

It seems to me that Paul has not so much changed his mind, but changed his perspective. In 1 Cor 15 he is speaking from the perspective of one who expects to be around when the day of resurrection occurs – he will be transformed while others are raised. It is the perspective of one who will be on earth when this happens, and is described accordingly. When we come to 2 Cor 5, he writes as one whose body has experienced great trials and has become like the worn out tents he so often worked to replace. Now he is thinking about things from the point of view of one who is certain he is going to die. How will I experience this? What will happen to me in relation to the embodiment of spirit that makes me human? And so he writes about the eternal dwelling in heaven that he will be given on his death so that his spirit will not be found ‘naked,’ ie disembodied.

It is not clear from the text whether or not this experience takes place at the ‘bema’ of Christ – the seat from which the local Tribune dispensed justice. However, my inclination at the moment is that it does because of the way the text flows. That, however, raises a whole lot more questions for another day.

Recently a friend encouraged me to use my blog to share things I’ve been studying, and since I recently completed the first year of an Open University MA in Classical Studies, I thought I’d share the end of year paper I wrote answering the question, ‘How important is an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology?’

I am hoping to write next year’s dissertation using material and literary remains from Roman Corinth to shed light on some aspect of the Apostle Paul’s correspondence with the early Christians there. Any comments and ideas would be welcome.

The first year of the course has been fascinating and successful for me and I’m really looking forward to the new session that starts in October. In the meantime, here’s the essay and I’d be happy to receive any thoughts on it.

Jared.

How important is an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology?

‘Artifacts can’t tell us anything about the past because the past does not exist. We cannot touch the past, see it, or feel it; it is utterly dead and gone. Our beloved artifacts actually belong to the present…

‘Somehow we have to take the archaeological materials that we have and through our questioning get them to give us information about the past.’ (Johnson, 2020, pp. 14 – 5, emphasis original; cf. Osborne and Alcock, 2012, p. 3)

It is in the light of comments such as Johnson’s that I will argue in this essay that an interdisciplinary approach to the study of archaeology is crucial to obtaining the fullest information from material remains and for understanding the lives of which they speak. However, the question posed for this essay begs the answer to two other questions that we must first address: what is ‘the study of archaeology’; what is ‘an interdisciplinary approach’? (I shall pass over the additional question, what is a ‘discipline’? (Rives, 2010, p. 98), and assume that it includes every skill that can be deployed in this enterprise.) I shall explore answers to these questions and then examine how the two relate to each other using examples from the city of Corinth and its material remains: pottery, coins and an inscription.

The ‘study of archaeology’ has a significant history and the concept(s) of what it is today is very different from that of a century ago and more. What is it now and how has it changed over time? For a brief historiographical taxonomy of methods for the study of archaeology I will draw on the American School of Classical Studies in Athens’ (hereafter ASCSA) explorations at Corinth from 1896.

Three eras of archaeological method over the period are helpfully laid out in ASCSA’s site guide (Sanders et al, 2018 pp. 24-5). Initially, excavations at Corinth were focussed on topography. The study of archaeology was about where important buildings were sited: temple, agora, homes, roads, theatre and forum, and large teams of non-specialist labourers were used to clear the ground.

In the second quarter of the twentieth century, it was typological and chronological concerns that predominated (Aldenderfer, 2012, pp. 309-11). What kinds of artefacts were being found and how did they relate to each other and their wider context of place and time? Can we discern a chronology through similarities among the materials discovered, cross-referenced to the various sites where they were found? However, the same basic method of employing local non-specialists continued, with the attendant inherent risks.

It was not until the 1960s, under the directorship of C. K. Williams II and amid the intellectual ferment of the time, that the focus shifted from monumental aspects of archaeology to place the human at the centre. This period also coincided with the ‘democratic turn’ (Hardwick and Stray, 2011, p. 3) in Classical Reception Studies. Together they reflect on how these remains may have been used originally by the people of their time and what information they can impart to us about these people and the kinds of lives they lived. ASCSA has published its findings extensively over the decades.

This does not mean that topographical, typological and chronological evidence is no longer important. Rather, it is placed within a new context where the dynamics of human processes are at the centre. Where, in the past, methods may have been developed on an ad hoc basis, with little or no theoretical assessment (Johnson, 2020, p. 16), the 1960s onwards saw the development of a ‘New Archaeology’ (Johnson, 2020, pp. 13-37) that grew out of a sense of dissatisfaction with previous archaeological work, its theories, methods and aims. By placing people at the centre, Archaeology was becoming a sub-discipline of Anthropology.

It would be an error to assume that in the present day there is a one-size-fits-all approach to the study of archaeology. There are varieties of approach of both theory and method. Rather than being a feature that simply fractures the study, perhaps these can be seen as a development with a positive impact on our understanding of material remains. Alternative theories and methodologies focussing their attention on the same data/artefacts, and advancing alternative possible interpretations, can enlarge our understanding rather than diminish it.

What emerged early on from new archaeology were groups identifying as ‘Processualism’ and ‘Post-processualism.’ These emphasise ‘the linkage between biological organisms (humans) and their environment’ (Schiffer, 2012, p. 665), which includes the available technology. Processualism relies heavily, therefore, on social theories allowing patterns to be discerned towards understanding the structure and dynamics of a culture (Schiffer, 2012, p. 666). Its aims were to ‘be more scientific and more anthropological’ (Johnson, 2020, p. 23, emphasis original), and its interest was in the community. Post-processualism is less of an identifiable ‘school’ and more of a movement of protest against what is seen as too positivist philosophical underpinnings of Processualism. Post-processualism presses the role of the individual as agent, provoking processualists ‘to embrace long-neglected research questions about, for example, ideology, power, and class, and to seek rigorous methods within a scientific epistemology to answer them.’ (Schiffer, 2012, p. 666)

The ‘study of archaeology,’ therefore, is a moving target, with theory and method in constant development and interaction. And if our ‘beloved artifacts’ cannot speak for themselves, how may we elicit and interpret the information they can divulge? Only by employing as wide a range of present-day disciplines as possible, that help to answer the many questions we may have – the more questions, the better (my own questions will be exemplary rather than exhaustive). Our present-day theories and methods need to be brought to bear not only on what is being discovered now, but also on remains recovered by previous generations of archaeologists. There will be lacunae in the chain of evidence and therefore no present-day investigation of previously discovered remains can be as rigorous as investigation on those found in situ today. The picture will be incomplete, but then the picture is always incomplete because the past cannot be recovered. And tomorrow’s advances in theory and method will be applied to today’s discoveries. We must make sure that as much data as possible is recorded and saved so that tomorrow’s advances will have as much as possible to work with.

It is important to note at this point that we do not need to provide detailed answers to all the questions we may have about artefacts referred to in this paper, only to illustrate the disciplines needed to answer them. However, from the literature available we will be able to indicate some answers. It is to how we can interrogate material remains that we now turn.

The material remains uncovered by ASCSA at Corinth include a wide variety of artefacts (see the range of essays in Williams and Bookidis, 2003). In truth, archaeology has always required people of different disciplines to carry forward its work, such as classicists, geographers, historians, specialists in pottery and numismatics, and people fit to dig. However, the extent to which disciplines cooperate will determine the extent of the information retrieved and how that information is interpreted. At this point, there is a basic question about the terminology we should use to describe this cooperation: should we speak of it as ‘multidisciplinary’ or ‘interdisciplinary,’ or do they mean the same thing? Both the ‘multi’ and ‘inter’ prefixes have a legitimate input to the cooperative concept: ‘multi’ reflects the wide range of disciplines that must be brought to bear; ‘inter’ reflects the nature of the interaction among these disciplines. The literature tends to use ‘interdisciplinary’ (e.g. Schaps, 2011, p. 12), but ‘multidisciplinary’ also appears to be implicit in how the term is used. Deciding on the more appropriate term is not easy. To illustrate my own understanding of the nature of the cooperation needed I will describe two scenarios. In the first, an artefact from Corinth is taken to a university and passed round several departments, each of which applies its own discipline to the artefact and writes an independent report on it. Thus, it is studied from the point of view of a multiplicity of disciplines, but without real interaction among them. In the second, an artefact from Corinth is placed on the table in a university conference room and scholars from various disciplines gather round the table. Each describes the artefact in terms of their discipline, but they are questioned and challenged by the others round the table so that the description is clarified (or complexified?) as far as possible through present theory and method. Only one report is written (although minority reports may be required to deal with competing interpretations). It is this second scenario I have in mind when I use either ‘interdisciplinary’ or ‘multidisciplinary’ to describe cooperative approaches. But which disciplines should sit round the conference table? That will depend on what is sitting on the table.

In the early years of the latter half of the twentieth century, there was a push to make the study of archaeology more rigorously scientific with new disciplines added to the mix, and we could now include such activities as soil analysis, carbon dating, DNA analysis and so on. But in the later years of the century, social sciences were also being adduced to interpret evidence: sociology, psychology, anthropology and others (Schaps, 2011, p. 12-3; Rives, 2010, p. 102). This gave rise to tensions that remain to the present day between the philosophical theories and methods of two very different kinds of scientific inquiry, and what can be known for certain through their application to material remains.

The disciplines needed to interrogate Corinth and its material remains will vary according to the remains being considered. Thinking first of Corinth as a whole, situated in Achaia on an isthmus, the Greek city was destroyed by the Roman army in 146BC, and largely uninhabited until Julius Caesar re-established it in 44BC as a Roman Colony that quickly grew in wealth and influence. But let us pause. How do we know this? Why did these things occur? Here we can bring to bear some of the more traditional disciplines of classical inquiry: geography and history, to reflect on the importance of Corinth’s situation and to investigate the story of its destruction and refounding, from ancient writers such as Strabo (1927, Geography, 8.6.20-3) and Pausanius (1918, Description of Greece 2), to the present; Latin and Greek, to translate annals, archives and inscriptions that may tell us who the colonists were, why they were sent and the constitution under which the Roman city existed (for inscriptions, see Kent, 1966); experts in the workings of the Roman Army who may be able to shed light on how the army related to every aspect of life in the Empire, including colonies (Pollard, 2010). But even this list of disciplines will only scratch the surface.

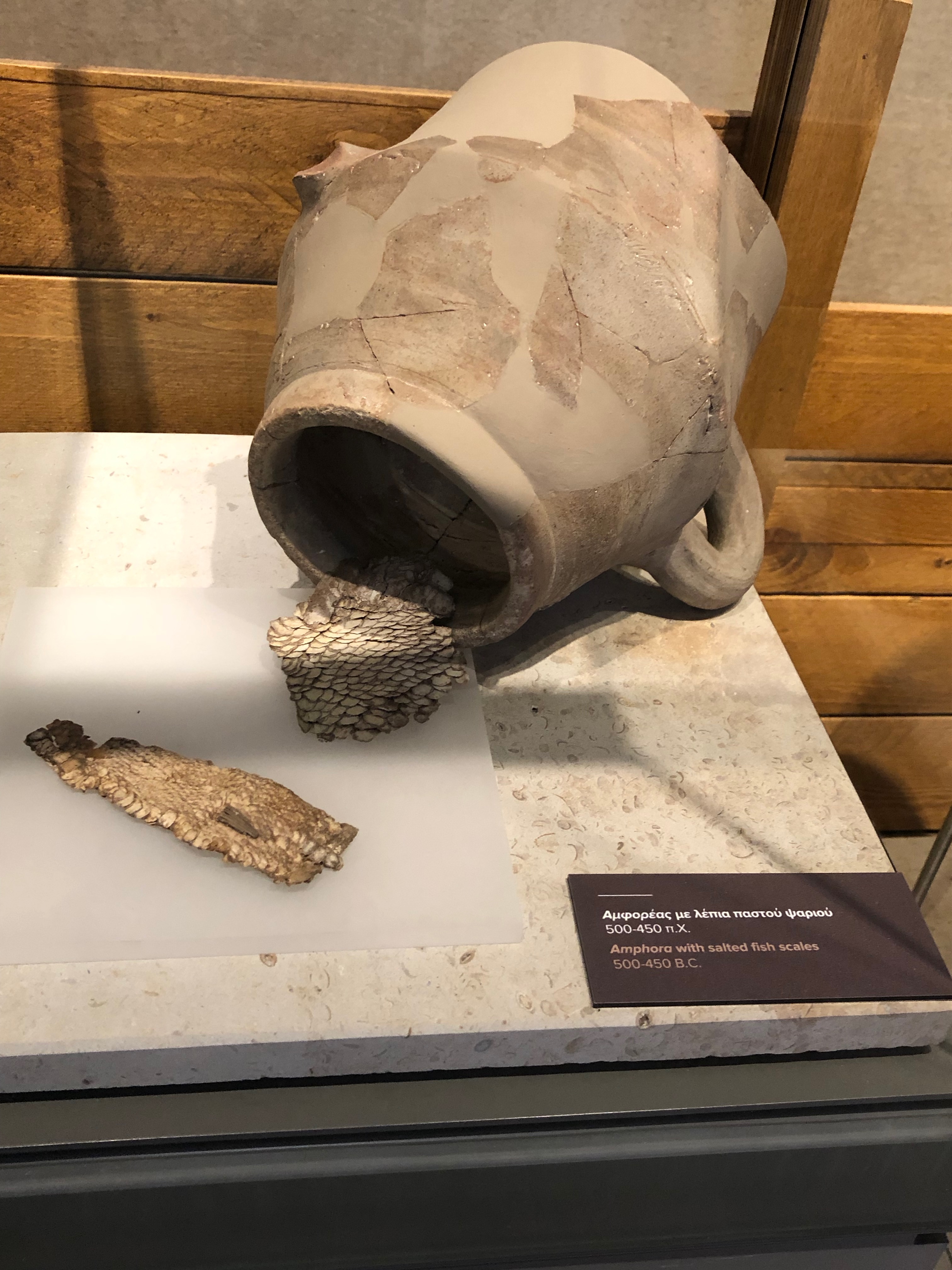

Let us now take three examples of artefacts found on the site of Ancient Corinth to exemplify how an interdisciplinary approach is needed: pottery, coins and an inscription. Corinth was known as a mass producer of pottery from pre-Roman times (Risser, 2003, p. 157; see Figs. 1-3 in the Appendix), and many examples have been found that span time from the eighth century BC, through Roman Corinth and beyond, within the city and elsewhere (see chapters 8-12, 19 and 24 in Williams and Bookidis, 2003; for examples, see Figs. 2 and 3 in the Appendix). How might we know if pottery found within the city was made in the city or elsewhere? What can we tell from residue within a pot? How can we discern the age of pottery and to which era it belonged? What about pottery found elsewhere, but made in Corinth? Can we identify it, and if we can, what does this say about the influence of Corinth in the eastern Mediterranean? We need disciplines that will help us understand processes of collection of raw materials, product design and decoration, and economic activity across the region, all diachronically over centuries. But, for a moment let us focus on one discipline relating to clay.

Clay is the basic material of ceramic production and there are deposits of various kinds around Corinth. Each deposit has clay minerals in varying quantities, and these can be identified by using X-ray diffraction. However, after clay has been fired, other methods must be used, such as ceramic petrology and chemical analysis (Whitbread, 2003, pp. 2-3). All these disciplines are highly scientific and technical and are not part of ‘everyday’ archaeological activity. However, they are necessary tools for grasping some of the significance of Corinthian pottery over a prolonged period. Working together they can begin to build a picture of the role this pottery played in lives across generations.

Ancient Corinth produced its own coins (for examples, see Fig. 3 in the Appendix), and Roman Corinth also had its own provincial mint from its foundation until the accession of Vespasian. It was re-established under Domitian, but minted fewer coins from then on. The coins were made of bronze, for which Corinth was renowned, but they have often been found badly corroded in the soil (Wallbank, 2003, p. 337).

Bradley Bitner writes that four methodological considerations are relevant to engaging with Corinthian coinage in Roman times (Bitner, 2015, p.161-76), and these are well worthy of consideration. First, this is Roman provincial coinage, rather than Imperial coinage, with implications for the time-frame, geographical setting and political authority under which the coins were produced. Second, we must measure what we can of the minting process from mining of the metal to the size of the coin and its image. And we must do this cognisant of the civic life of the city and its duoviri for ‘not only does the money give us evidence for the men; the men gave us the money.’ (p. 164) Third, there needs to be investigation of how Corinthian coinage circulated within the wider area to gauge its impact on the regional economy. Finally, since numismatic iconography presents a face to the world, there needs to be careful examination of coin stamps to try to understand how the city saw itself, and, perhaps more importantly, how its officials wanted it to be seen by the world.

What questions, then, might we ask of these coins to shed light on the life of the city and its surrounds? How big are they? Of what value are they? How pure is the metal? Is there metal debasement over time? What is the significance of the iconography? Might the number of coins found provide any indication of the strength of economic activity locally? Were Corinthian coins found elsewhere, and/or non-Corinthian coins found in Corinth (see Appendix, Figs. 4 and 5)? What might that tell us of economic activity in the region? How might the iconography of coinage cast light on the civic identity of Corinth? Can interpreting duovirate coinage help us put together a Corinthian chronology and/or tell us something about its officials? Could a longitudinal examination of the iconography of Corinthian coinage tell us anything about the trajectory of the city’s relationships with Rome and Greece? Could the residual material adhering to the coins hold any DNA that, when analysed, could shed light on those who handled it? It is clear that many of these questions may be addressed in ‘everyday’ numismatics, but the net must be cast more widely to include metallurgy, economics, DNA analysis, iconography and the sociology of urban and imperial identity. Interdisciplinarity is a sine qua non for this inquiry.

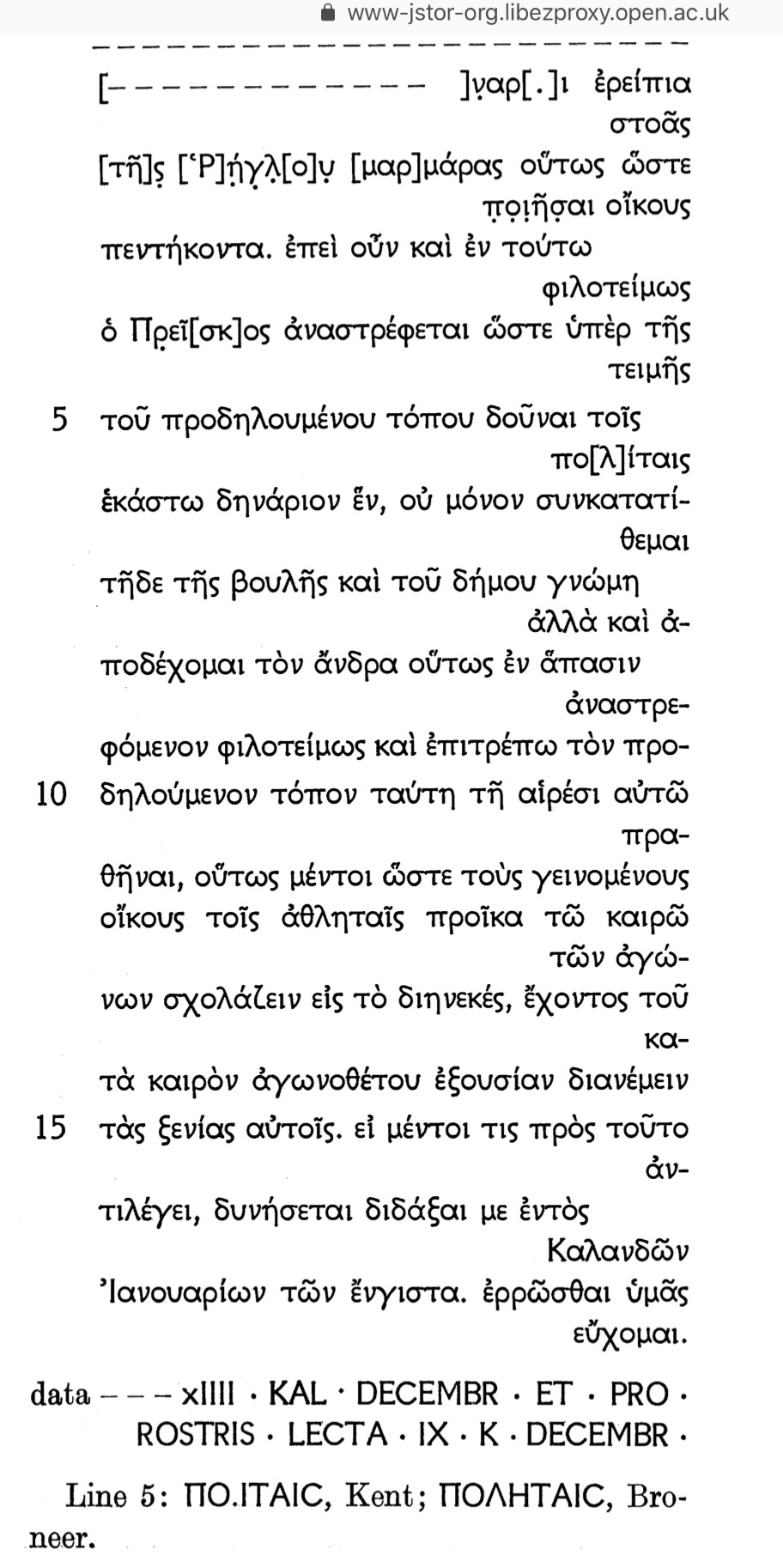

We turn, finally, to an inscription. As noted above, from 44BC Corinth was a Roman Colony. The question of language, therefore, arises: how were Latin and Greek used in Roman Corinth, and how did the relationship between the languages develop? The inscription in question (Kent, 1966, p. 120 and Plate 26, see Appendix, Fig. 6), inscribed on a limestone block, was read on 23 November of an unknown year in the second century AD. Thirty-one lines of it are in Greek, and one, final, line in Latin. It appears to have been official communication (Kent, 1966, p. 120; Bitner, 2016, p. 185). In addition to the need for translation, there are questions prompted by this inscription. Where did the limestone come from? Was the inscription commissioned and written elsewhere? Who commissioned it, and why? Why was most of it in Greek? Why, with so much Greek, was there any Latin at all? Was the Latin an official archival reference? What light could this inscription shed on the ongoing relationship of Roman Corinth with Rome and Greece?

For us to answer these questions we need not only translators and historians, but also geologists and chemists, who may be able to identify possible sources for the limestone. We need experts in Roman administration in the colonies to shed light on why and how public announcements were made, what style of fonts were used in them, and how they were recorded for posterity. Only thus will this inscription give up more of its information and speak to us about the city where it was read.

It is clear from the range of skills needed to answer the questions we have raised about the artefacts from Corinth that wide-ranging disciplines – humanities, historical, linguistic, scientific and social-scientific – need to be applied to help answer them, and most of these disciplines are not ones in which humanists and social scientists have particular training (Wylie and Chapman, 2015, p. 4). Specialists are required, though not all specialists will be required on every occasion. Regardless of how many are involved at any one time, it is the depth of their interaction that will lead to greater understanding. The answers they give to the questions must be assessed and interpreted against the backdrop of our wider knowledge of the historical and cultural context in which the artefacts were found. What stories do we think they tell? Which leads us to interpretation.

The issues surrounding the interpretation of facts are not easy. ‘Material evidence is inescapably an interpretive construct; what it “says” is contingent on the provisional scaffolding we bring to bear.’ (Chapman and Wylie, 2016, p. 6) Our personal identity, historical situatedness and biases place us in danger of constructing our interpretation of the evidence in ways that are not justified. Of course, others are in the same boat, but as we explore possibilities together from a range of disciplines and personal situations, a more fruitful and nuanced picture can emerge. Interpretation, therefore, must be ‘an ongoing iterative process’ (Wylie and Chapman, 2015, p. 13) that must be approached with ‘epistemic humility’ (Chapman and Wylie, 2016, p. 10).

In conclusion, it is only as disciplines work in humble cooperation, informing and challenging one another’s work, that a fuller picture can be painted of the life and social settings of ancient communities. Schaps broadly agrees with the assertion that no one scholar can have the required range of expertise and, as a consequence, he sees the need to ‘produce less departmentalized classicists.’ (Schaps, 2011, p. 13).’ To achieve this, Wylie and Chapman urge that archaeology must be ‘a dynamic trading zone…building an expansive network of technical, empirical, theoretical exchange (2015, p. 17) This is an ambitious aim for carrying forward the study of archaeology so that it may give us the best possible insights to the lives of people in the past. An interdisciplinary approach is not simply important; it is essential.

Jared W. Hay, May 2019

Bibliography

Alcock, Susan E. and Osborne, Robin, Editors (2012), Classical Archaeology (Second Edition), Blackwell, Oxford.

Aldenderfer, Mark (2012), ‘Typological Analysis,’ in Silberman, Neil Asher (2012), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition, Vol. 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Bitner, Bradley J. (2015), ‘Coinage and Colonial Identity: Corinthian Numismatics and the Corinthian Correspondence,’ in Harrison and Welborn, 2015, pp. 151-87.

Bitner, Bradley J. (2016), ‘Mixed Language Inscribing at Roman Corinth,’ in Harrison and Welborn, 2016, pp. 185-218.

Chapman, Robert and Wylie, Alison (2016), Evidential Reasoning in Archaeology, Bloomsbury Academic, London.

Chapman, Robert and Wylie, Alison, Editors, (2015), Material Evidence: Learning from archaeological practice, Routledge, London/New York.

Hardwick, Lorna and Stray Christopher (2011), A Companion to Classical Receptions, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford.

Harrison, James R., and Welborn, L. L. (2015), The First Urban Churches 1: Methodological Foundations, SBL Press, Atlanta.

Harrison, James R., and Welborn, L. L. (2016), The First Urban Churches 2: Roman Corinth, SBL Press, Atlanta.

Johnson, Matthew (2020 – sic), Archaeological Theory: An Introduction, Third Edition, Blackwell, Oxford.

Kent, John Harvey (1966), Corinth: Volume VIII Part III: The Inscriptions 11926-1950, ASCSA, Princeton.

Osborne, Robin, and Alcock, Susan E. (2012), ‘Introduction’ in Alcock and Osborne, 2012, pp. 1-10.

Pausanias (1918), Description of Greece: Books 1-2, LCL, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA/London.

Pollard, Nigel (2010), ‘The Roman Army,’ in Potter, 2010, pp. 206-27

Potter, David S. Editor (2010), A Companion to the Roman Empire, Blackwell, Oxford.

Risser, Martha K. (2003), ‘Corinthian Archaic and Classical Pottery,’ in Williams and Bookidis, 2003, pp. 157-65.

Rives, James B. (2010), ‘Interdisciplinary Approaches,’ in Potter, 2010, pp. 98 – 112.

Sanders, Guy D. R., Palinkas, Jennifer, Tzonou-Herbst, Ioulia, Herbst, James (2018), Ancient Corinth Site Guide (Seventh Edition ), American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton.

Schaps, David M. (2011), Handbook for Classical Research, Routledge, London/New York.

Schiffer, Michael Brian (2012), ‘Processual Theory,’ in Silberman, Neil Asher (2012), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition, Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Silberman, Neil Asher (2012), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition, Vols. 1-3, Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York.

Strabo, (1927), Geography: Books 8-9, LCL, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA/London.

Wallbank, Mary E. Hoskins (2003), ‘Aspects of Corinthian Coinage in the late 1st and early 2nd Centuries A.C., in Williams and Bookidis, 2003, pp. 337-49.

Whitbread, Ian K. (2003), ‘Clays of Corinth: the study of a basic resource for ceramic production,’ in Williams and Bookidis, 2003, pp.1-13.

Williams, Charles K. II and Bookidis, Nancy (2003), Corinth: Results of excavations conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. XX, Corinth, The Centenary: 1896-1996, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton.

Wylie, Alison and Chapman, Robert (2015), ‘Material Evidence: Learning from archaeological practice,’ in Chapman and Wylie, 2015, pp. 1-20.

Appendix 1

All photographs taken by the author, except Fig. 6.

At the suggestion of Jim Gordon, I wrote this short piece for his blog, Living Wittily, as one of a series on the books of Eugene Peterson, one of the outstanding shapers of pastoral ministry and spirituality in the last half century. Peterson at one point helped rescue me through his ‘Under the Unpredictable Plant’ but here I comment briefly on his style and aims in Reversed Thunder.

Reversed Thunder is not, by Peterson’s own admission, ‘a work of expository exegesis (xii).’ ‘Mostly I have enjoyed myself. I have submitted my pastoral imagination to St John’s theological poetry, meditated on what I have heard and seen, and written it down in what I think of as a kind of pastoral midrash (xii).’

Those familiar with his canon will recognise the themes in this short quote: pastoral, imagination, theology, poetry, meditation, midrash – and pleasure. He applies his fertile mind to Revelation and unpacks a series of ‘last words’ – on Scripture, Christ, Church, Worship and seven others – working his way through the Apocalypse as he does so. It is a book full of quotable quotes.

What is it that grabs people, especially Pastors, about Peterson’s writing? Here are a few examples.

The breadth of his reading. Pastors are bibliophiles, but often in certain areas of biblical studies or theology. Peterson has read, and in this book draws on, theologians and exegetes from across the centuries, but also from poets, novelists, literary critics and preachers. He soaks himself in words and brings them to bear on the text of Revelation to illuminate its meaning and arrest his readers.

The depth of his reflection. Peterson is enthusiastic about Scripture and for decades has chewed on it, then he gave us the benefit of his ruminations. Often the words are simple, but the thoughts expressed are profound, and strike home like a sharp double-edged sword, as in his comments on Christ and the Apocalyptic image of military violence (37). Words for today’s politicking.

The beauty of his language. I have no idea who edited this book, but I sense their task was easy. Peterson has a way with words that make this work a joy to read slowly, savouring the flavours that infuse it. Technical language is rare, whereas the skill of the wordsmith abounds, transporting the reader by disciplined use of a sanctified imagination into the son et lumière world that is the Apocalypse. He is an artist in his use of words, just like John the Divine.

His passion for pastoral work. Preaching, prayer, worship, spiritual direction: these are the forces that shape Peterson’s style and rhetorical purpose. He says that his primary question here is about how Revelation will work among the people he pastors (xiii). It is not a book of predictions. It is a book that spoke to the pastoral situation of the church of the first century and speaks now to ours. ‘In the Revelation we are immersed not in prediction, but eschatology: an awareness that the future is breaking in upon us. Eschatology involves the belief that the resurrection appearances of Christ are not complete (21).’

Revelation is a book that touched Peterson’s own soul. ‘What walking through the Maryland forests does to my bodily senses, the Revelation does to my faith perceptions (x).’ We are the beneficiaries of these perceptions, for in this work he not only teaches us what to think about Revelation but how to think about it – and how to respond to it in our time.

Jared Hay, 30 October 2018.